Cracking the Nut: Chestnut Unit Economics

In our last post, we discussed the market opportunity for chestnuts, an emerging perennial staple crop for the Eastern United States. The post below provides an introduction to the unit economics of chestnuts, including factors and risks impacting yield, pricing, and farm-level profitability.

Chestnut Yield

Sound design and layout of a chestnut agroforestry system is not only fundamental to long-term management and operation, but also implicates yield over the lifetime of a new planting.

In general, the recommended approach for chestnuts is to plant at “double density” of 20’ x 20’, or 109 trees per acre, with the expectation that trees will be thinned to their final spacing of 40’ by 40’, or 52 trees per acre in later years; double density planting also increases yields in earlier years of orchard establishment.

Thinning trees and selecting for the most productive specimens can occur as early as years 8 - 12 (Beccaro et al 2019).

Chestnuts begin to produce nuts as early as year 5, with commercial production beginning in years 8 to 9 and mature production by year 15. While fully productive trees can produce 60 lbs per year at maturity, we model a conservative estimate of 30 to 45 lbs per tree per year (Michican State University). Chestnuts yield annually and can produce nuts for more than 60 years.

Established chestnut orchards in the US produce between 2,000-3,000 lbs per acre (UC Davis; UMCA), though average productivity can exceed 4,000 lbs per acre globally, nearing 5,000 lbs/acre in China (Freitas et al 2021). Evidence from tree crops such as apples indicates that yields in agroforestry and monocrop systems are comparable (Staton et al 2022). In our case, high chestnut densities will be maintained, meaning yields of 2,000-3,000 per acre can be expected from well-designed and managed chestnut systems.

Export Market - Prices

Pricing for US grown chestnuts varies between $2.72/lb average via export markets and $5.50/lb for conventional wholesale, with farmers typically selling out of fresh nuts within 3 to 4 months after harvest.

Figure 1 - Time Series (5 Year) for Exports by Month (USDA FAS)

In-shell chestnut exports from the U.S. have averaged $2.72/lb over the past 5 years:

Low: $2.01

High: $3.89

US Market - Prices

According to the FAO, Chestnut Growers of America, and the University of Missouri’s Center for Agroforestry, domestic prices for in-shell chestnuts over the past 5 years range from $4.00 - $8.50 for conventionally-grown nuts, and $7 - $12.50 for organically-grown nuts.

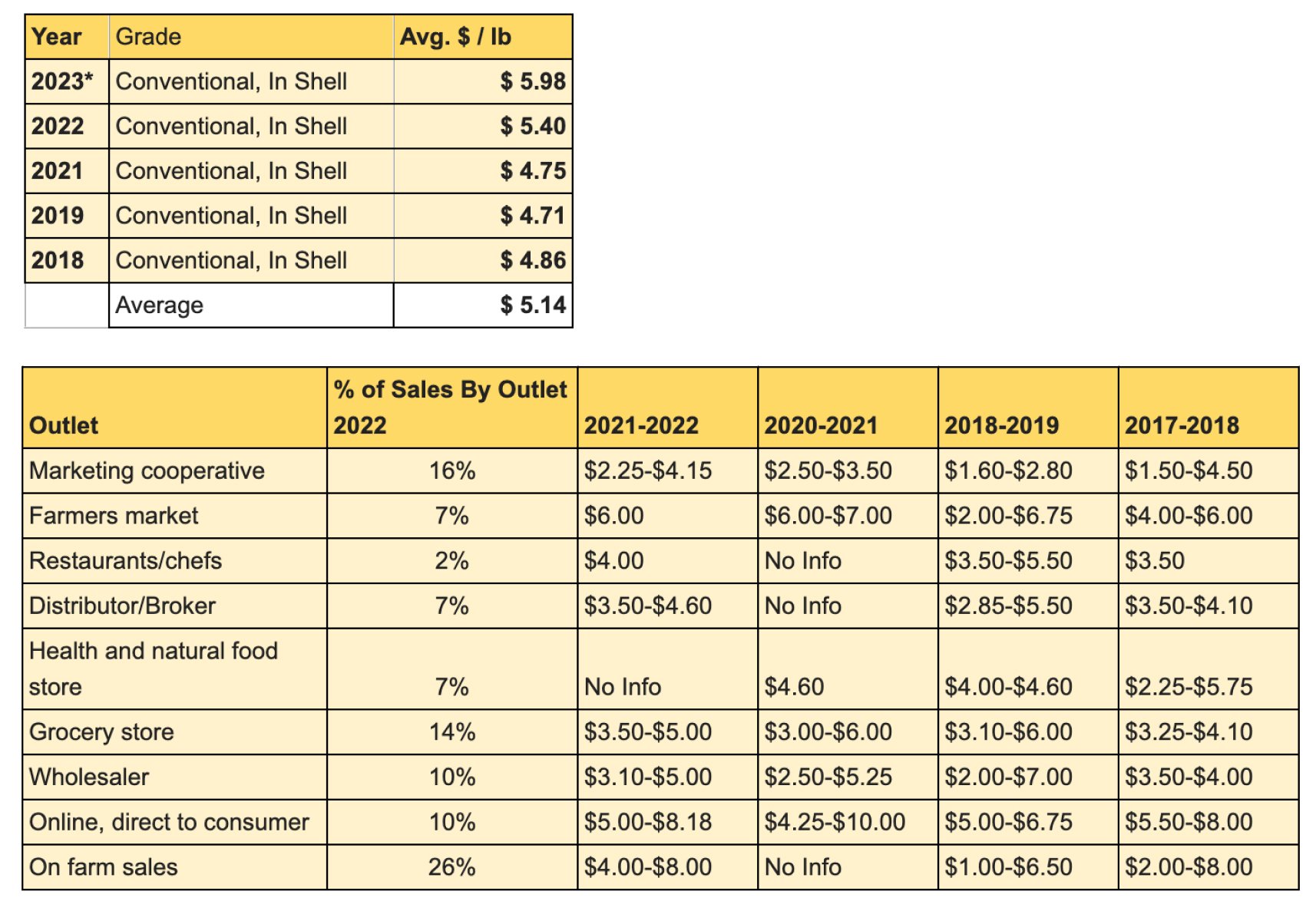

Figure 2 - Average Domestic Prices (2018 - 2023)

Compiled data derived from domestic orchard and co-op prices.

*Note that 2023 orchard production was low due to a rare frost across the Eastern US in May after a hot March & April. This decreased supply likely played a role in such elevated pricing for 2023.

Figure 3 - Domestic Prices by Sales Channel (2017 - 2023)

2017 to 2021 pricing data from a survey of grower and co-op channels by Chestnut Growers of America collects data across market channels with grower & coop reported price ranges.

Figure 4 - Organic Price Premium

For a historical viewpoint on price, University of Missouri conducted a market report that showcased domestic conventional & organic pricing by sales channel in 2005 (Center for Agroforestry, 2021). In this study, certified organic chestnuts on average sold for 25% higher prices than conventional chestnuts.

Given that all imported chestnuts must be fumigated prior to entry into the US, foreign producers are unable to fill this organic niche, which offers an advantage for US producers growing chestnuts organically. Because chestnuts are a fresh nut that requires refrigeration, imported chestnuts can also suffer from quality concerns (dryness and/or mold) if not properly stored during shipment.

Farm-Level Returns

Farm-level Internal Rate of Return (IRR) can vary dramatically based on a variety of factors, including cost of land & capital, operational efficiency, farm-level productivity, and price realization.

After accounting for land cost as a premium lease rate to the farm operation as well as assuming productivity and price realization are within the domestic averages mentioned above, farm-level IRR’s can range from:

Low: 8.5% (30 lbs per tree at $2.50/lb)

High: 28.1% (50 lbs per tree at $4.50/lb).

The farm pictured to the left was modeled in Overyield, Propagate’s agroforestry analytics platform. Farm-level scenario modeling incorporates price variation across sales channels, risk, management costs, and other factors that impact farm-level IRR. Assumptions for the farm pictured include 6-12 month full field prep, bare root nursery stock, tree protection, mechanical harvest, and wholesale pricing, resulting in an IRR of 24.98%.

Risk Mitigation

Supply-Side Risks

The Chinese chestnut co-evolved with and is naturally resistant to the major pests and pathogens that currently threaten European, Japanese, and American chestnuts— chestnut blight and ink disease, which together have contributed to significant declines in European chestnut production (Freitas et al 2021).

Droughts in Southern Europe will exacerbate these impacts to European production (Freitas et al 2021). In North America, novel breeding strategies are rapidly identifying Chinese hybrids with improved resistance to these major pathogens (Miller 2020), and many parent lines with improved disease resistance are already commercially available to growers (Revord 2021). The genetic makeup of American orchards will offer an advantage the US chestnut industry relative to competing markets, as will the relatively more favorable climate of the Eastern US. The Eastern US receives roughly 50% more precipitation than the major chestnut growing regions of Europe, providing a buffer to producers from drought related impacts. The increasing unpredictability of winter thaws and spring frost events may incur yield losses for the chestnut industry, as with most crops, but frost avoidance through bloom delay is present in specific commercially available cultivars, though breeding to improve this trait is ongoing (Revord et al 2021; Warmund et al 2011).

Other introduced pests and diseases that impact North American chestnut yields include anthracnose, a fungal pathogen, and the chestnut weevil. Losses caused by these pests can be managed through proper post-harvest handling and storage, combined with a pro-active Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy that involves selecting resistant cultivars, monitoring pest life cycles, and timely interventions. Other emerging pests include gall wasp, which can in part be managed biologically by naturalized parasitoids (Demard and Cave 2021), and oak wilt, whose incidence can be prevented by timing pruning during vectoring insect dormancy (ISU 2023).

Demand-side risks

In the tree nut sector, oversupply and alternate-bearing yields can lead to price fluctuations, though expanded processing capacity and growth in the export market can ease these impacts (Davis 2021). Chestnuts are not alternate-bearers, meaning their prices will remain more stable year over year, though frost and rainfall can impact yield. Moreover, a historical precedent exists for price stability as overall supplies increase within the pistachio industry (See Figure 1 in our previous post). Chestnut producers can replicate the success of the pistachio industry by executing on international demand, identifying consumer trends, and building domestic awareness.

Conclusion

The profit potential of chestnuts depends on farm-level management, price realization, and risk mitigation. A growing domestic market for chestnuts presents an opportunity for import substitution with higher quality US-grown chestnuts, which are uniquely positioned to capture organic premiums.

If you are interested in learning more about chestnuts and whether or not they might be a fit for your land or portfolio, contact us here. Propagate can provide due diligence and economic modeling support for chestnuts and a range of other agroforestry project types.

Propagate is a regenerative agriculture platform that makes it easy for farmland owners to design, plant, and manage agroforestry systems so that they can increase the cash yield of farmland.

Photo of a chestnut-hay alley cropping system in Maysville, Kentucky.

The Information provided herein is provided without representation or warranty of any kind. The Information is to be used for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation or any kind of purchase or sale of any security or investment. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment or other advice. The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record, simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or over compensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Propagate makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Any other use, reproduction or transmission of the Information, in whole or in part, is prohibited except by written permission from Propagate Group, PBC (“Propagate”).Data & Referenced Materials compiled by Propagate and Agroforestry Partners

References:

AGMRC. (2024). Chestnuts. Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Retrieved from [Link].

Bar Am, J., et al. (2023). Consumers Care about Sustainability—and Back It up with Their Wallets. McKinsey and NielsenIQ, 24 Feb. 2023.

Barbaro, M. R., et al. (2020). Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in the Context of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients, 12(12), 3735. [Link].

Beccaro, G., et al. (Eds.). (2019). The Chestnut Handbook: Crop & Forest Management (1st ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Link].

Boriss, H. (2005). Commodity Profile: Pistachios. Issue brief. Davis, CA: Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, pp. 1–7.

BOZOĞLU, M., et al. (2019). Türkiye Kestane piyasasındaki gelişmeler. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım ve Doğa Dergisi, 22(1), pp. 19–25. doi:10.18016/ksutarimdoga.vi.430319.

Casey, C. (2022). 8 Carbon-Neutral Brands Aiming to Cut the Food and Beverage Industry’s Emissions. Food Dive. Retrieved from [Link].

Cernusca, M.M., et al. (2012). Post-purchase evaluation of U.S. consumers’ preferences for chestnuts. Agroforest Syst, 86, 355–364. [Link].

Chestnut Growers Inc. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Crawford, K. (2023). Corn, soybeans and ...chestnuts? Ohio farmers find new uses for the uncommon crop, WOSU Public Media. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Davison, B. et al. (2021) OVERCOMING BOTTLENECKS IN THE EASTERN US CHESTNUT INDUSTRY: An Impact Investment Plan. rep. Savannah Institute. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 2024).

FAOStat. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Fang, M., et al. (2019). A Hard Nut to Crack: Identifying Factors Relevant to Chestnut Consumption. Food Distribution Research Society. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Guiné, Raquel. “A Review of the Use of Chestnut in Traditional and Innovative Food Products.” Journal of Nuts, vol. 14, no. 1, Mar. 2021.

Fresh/Dried Chestnuts (2022). The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Available at: [Link].(Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Freitas TR, et al. (2021). Influence of Climate Change on Chestnut Trees: A Review. Plants (Basel), 10(7), 1463. doi: 10.3390/plants10071463.

Gershon, L. (2018). When Chestnuts Were an Everyday Food. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved from daily.jstor.org/when-chestnuts-were-an-everyday-food/

Gold, M., et al. (2005). Chestnut Market Analysis Producers’ perspective. rep. Columbia, MO: UMCA, pp. 1–32.

IMARC Group. Chestnut market size, share, industry report 2024-2032. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: March 2024).

MacFarland, K. (no date). Chestnuts: A perennial opportunity for Northeast Farms, USDA Climate Hubs. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Malone, T. (2021). Identifying Factors Relevant to U.S. Chestnut Consumption. Chestnut Grower, Spring 2021.

Marciniak-Lukasiak, K., et al. (2022). The Influence of Chestnut Flour on the Quality of Gluten-Free Bread. Applied Sciences, 12(16), 8340. [Link]

Reed, L. (2020). Study concludes Americans self-diagnose to adopt gluten-free diets, Nebraska Today | University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved from [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Revord, R.S., et al. (2022). A roadmap for participatory chestnut breeding for nut production in the Eastern United States. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.735597.

United Nations Comtrade. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

University of New Hampshire Extension, Restoring the American Chestnut. Available at: [Link] (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

USDA/NASS QuickStats, United States Department of Agriculture National Statistics Service. Retrieved from: [Link]. Accessed 2024.

Vossen, P. (1996, March/April). Chestnuts. UC ANR Small Farms Network. Retrieved from [Link].